When Laura Knight returned to Oakhill, her rented cottage near Newlyn, from a sketching trip was she confronted by a vision which immediately inspired her to a flurry of painting. Waiting in the garden was a young woman, with pale Irish skin and red-blonde hair, looking for work as a model.

Knight, whose career was blossoming by the time she and her husband Harold established themselves among the flourishing artist community of Newlyn, recalls in her autobiography : “She looked a sunflower herself among the sunflowers. I engaged her at once.”

The girl was Dolly Henry, a 20 year from London who had arrived at Newlyn a few months earlier with her lover John Currie, a modestly successful artist who mostly earned his living as a drawing master at Bristol School of Art.

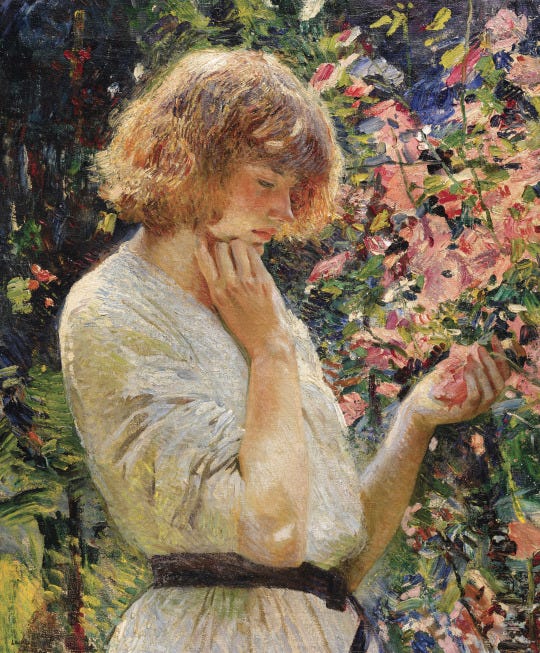

Knight’s working relationship with Dolly was fruitful and Laura produced several works in a short spell, including a striking image of Dolly, amidst the flower garden of Oakhill, which was later bought by the wealthy collector Lord Leverhulme after he saw it at an exhibition at London’s Grosvenor Galleries.

Yet the partnership was brief and ended suddenly. Laura writes: “I was never able to finish the last picture I was doing; she left suddenly – in a panic….”

There was good reason for Dolly to flee Newlyn. She was dreadfully afraid of Currie, who she claimed had tried to kill her and was again threatening to do it.

Laura Knight thought she was talking “sensational nonsense” until a few weeks later she read in The Cornishman daily paper “of a murder sensation - Currie had found her - shot her and shot himself. Both were dead.”

I might never have known of the “Paultons Square Tragedy”, if I hadn’t been reading a musty old copy of Oil Paint and Grease Paint, Laura Knight’s first volume of autobiography, from 1936, in which she chronicles her journey from birth in Long Eaton to her election to the Royal Academy. I often pick up old autobiographies, there’s an authenticity about them which subsequent biographies somehow filter out. It’s an excellent read, full of detail about the Knights, their circle of friends and their struggle to establish what became glittering careers. I particularly love the way Laura Knight sets down on paper exactly what she sees through the artist’s eyes which made her one of England’s great impressionists, female or male, of the 20th century. A few small gems before we leave Laura’s book pick up Dolly Henry’s story elsewhere:

At a funeral in Staithes: “By the head of the trestle are white-faced old people we have never seen out before. Old men’s black pilot-cloth coats hang loose over their guernseys…here is a beaver hat that must be a hundred years old…”

On the Yorkshire moors: “You just had to jump and race and shout upon those lonely heights, for the very joy of being there - alive. A switchback road ran on for ever between a land of waist-high heather, of broom and gorse that bloomed in the Spring. Larks sang perpetually in the sky. On a hillock a black-faced horned sheep stamped at you as it stood over its new-dropped lamb. Danby Beacon rose black out of the distant moors to touch the clouds that rolled above”

And from a shippen: “..comes the sound of clanking pails and a soft swishing throb, a tinny note. Through the open door we see a blue-white trickle between the red fingers of a farmer’s boy as he pulls and coaxes the mauvish teats. From under his cap a tawny tuft of hair mingles with the cow’s own plushy coat of deepest red and purest white.”

She hardly needs to put brush to canvas, so painterly is her prose and it was the vision Laura saw in that flower garden which immortalised the unfortunate Dolly, so soon to die in Currie’s jealous fury.

Dolly’s murder is not a widely-known event more than a century later, and it didn’t make the headlines then as it might have done in calmer times. This was, after all, October 1914 in the first few fevered months of World War One. Most people had their own worries and the newspapers were focussed on the conflict in France. In a headline on Dolly’s inquest report the event was dismissed as a “tragedy” - almost as if the pair had been in a road accident, or drowned at sea.

Today we might describe the events very differently. Dolly was exploited and physically abused by an older, more worldly man. And when she tried to escape a suffocating relationship, by finding a new partner, Currie’s jealousy boiled over. He hunted her down, burst into the flat she had rented in Chelsea and blasted her four times with the automatic pistol he had threatened her with before. Then, maybe remorseful or simply too cowardly to face the consequences, John Currie made a botched job of shooting himself.

Currie had shown early talent as an artist, but he had a tough start to his career. Born in Stoke-on-Trent as the illegitimate son of an itinerant railway “navvy” and a local girl, his first job was painting ceramics in local potteries. His talent was sufficient to get him a place at art college in London and he found a living as a master of life painting at Bristol Art School. He was remembered by the men in his artistic circle as a rare talent, snuffed out too young, after falling for what the author and art collector Michael Sadleir, described as a woman who was “lascivious and possessive to the last degree”. Sadleir, along with Mark Gertler and Augustus John, were keen apologists for Currie and would have history believe he was as much a victim as a villain. Sadleir wrote later that Currie’s painting “blazed with genius”. Augustus John - himself no stranger to deceit and questionable moral behaviour - wrote of Dolly: “She was an attractive girl - or used to be when I knew her first, but seemed to have deteriorated into a deceitful little bitch”

There is no way of knowing for sure whether these men believed Dolly was malevolent or were simply spouting misogynistic piffle inspired by fraternal loyalty. But we know for an absolute fact that Currie was a weak and jealous man with little to recommend him. He was a deceiver who left, in Stoke, a wife and young child without a penny of support and who then persuaded Dolly - a 17 year old whom he had met when she was a model in a dress shop - to go through a form of marriage when she had no idea he was committing bigamy.

By the time of the murder they had been together for three years, although Dolly made several attempts to end the relationship in her last few months of life. Currie was frequently violent and abusive towards Dolly, leaving her with bruising and black eyes - and he threatened worse. Only weeks before the meeting in Oakhill’s garden, Currie had taken Dolly to a nearby cliff-top and threatened to throw her off; she had just run away from him in genuine terror when she met Laura Knight.

There is, however, little hint of Dolly’s looming predicament in Laura Knight’s artwork. Dolly appears serene and beautiful, lost in thought as she poses among marsh mallow flowers in the Oakhill garden. Nor did Knight make any mention of the model’s demise when the work was exhibited the following year in London and was bought by Lord Leverhulme. Knight herself believes he never knew the story before Mallows.

I have managed to unearth contemporary reports of the double inquest conducted by the Chelsea coroner Mr C Luxmore Drew just a couple of weeks after the murder and there’s clear proof of long-standing abuse and violence on Currie’s part. When giving evidence both Dolly’s mother, Kate Henry, and Currie’s long-suffering wife Jessie give detailed accounts of previous violence by Currie towards Dolly.

Kate Henry told how Currie had visited her home and asked permission to marry the teenage Dolly - giving no clue he already had a wife and son. Later when Dolly visited she had scratch marks on her neck and said Currie had held a knife to her throat but said Currie had begged for forgiveness. In a letter from France, where the couple were on a painting trip in 1912, Dolly wrote to say she had a black eye and was forced to stay indoors where she could not be seen. On another occasion Dolly came home because Currie was “knocking her about” but went back to him after he wrote begging again and promising Mrs Henry he would not repeat the behaviour.

There is a clear pattern of escalating and persistent physical violence and threats of worse - plus repeated returning to a violent partner by the abused woman. Our more enlightened laws of today would have clearly recognised Currie’s actions as coercive control and systematic abuse and Dolly might have been able to turn to the authorities before the fatal shooting.

But from the inquest evidence the conclusion was inevitable. Having taken up with a new boyfriend after her escape from Cornwall, Dolly took two rooms in a lodging house at 50 Paultons Square, Chelsea - now an elegant terrace of multi-million pound homes, but then a seedier part of town. She had only lived there two weeks when, at 7-30 in the morning, other lodgers heard an argument and then several shots. Joseph Hewitt who lived in a front room on the ground floor rushed up the stairs to find a young woman in a pink dressing gown with blood on her chest. With another neighbour, a nurse called Jean Wilson, he helped carry the dying woman into a nearby room. Then moans were heard from upstairs and a policemen, who had been passing when the shots were fired, went into Dolly’s bedroom and found the injured Currie lying on the bed. On the floor lay a Webley & Scott pistol and when the PC asked Currie why he had shot Dolly he would only say “I loved the girl”.

Currie survived a couple of days in hospital before succumbing to his wounds. In his lodgings police found various letters, some written to Dolly but never sent and one to his wife. It was clear he intended to kill the girl. “My motive is that Henry deserves death for her damaging untruths and the ruin of my career…I am thoroughly decided that she is a nuisance better out of the way altogether. Although it means my going too, I had rather that than this everlasting trouble with her.”

As for Laura’s reaction to Dolly’s death, I wonder whether she felt any regrets about not taking more seriously the girl’s lurid story? In her autobiography she admits she dismissed the stories of a violent and obsessive lover as “sensational nonsense”. Would the story have had a different ending if she had intervened?

Laura Knight’s painting of Dolly, which she titled “Mallows” but which was catalogued as “Marsh Mallows” when it appeared at a Sothebys sale in New York in 2018 is now in private hands having achieved a sale price of half a million pounds.

Riveting and totally disturbing, Peter. Thank you for bringing Dolly's story to the light of day. You write with great sensitivity about her short life and horrible death. She must have imagined herself free of him, only to find the nightmare back before her. And to have those men try to put the blame on her for her own murder!

This is a tremendous piece. I agree that Laura Knight's writing is as accomplished as her painting.

The painting of Dolly by Currie is haunting me. Only last year I was standing in front of it at the Potteries Museum and Art Gallery and remarking to my husband how contemporary it looks. I had no idea of its history. Not long after it appeared in Substack notes, and someone made the same observation. Now here it is in your article and I get to find out what happened to the sitter.

The hypocrisy inherent in how society judges the actions of men and women never ceases to infuriate me, and you lay out the double standards beautifully and with great insight. Thank you!