Fame, fortune and glittering prizes

So why have you probably never heard of this hugely succesful painter?

What would you say were the chief characteristics which would guarantee lasting fame and admiration for an artist and ensure they were known to students and collectors for decades after their death?

Winning all the premier prizes at art school would be a good start, don't you think? Add to that decades of laudatory coverage of your newest works at Royal Academy exhibitions in the popular press and a clutch of Royal commissions from a King and Queen who would pop round to your studio for tea.

And this artist did not just attract celebrity coverage, but won the respect of his peers through election as a Royal Academician and was chosen as one of the first ever official war artists, illustrating the horrors of WW1 for the great galleries and memorials of his age.

My mystery artist has all of these achievements - and more - so who am I thinking of? Sargent? Orpen? Clausen? Nash? It could be any one of dozen names of names from the Victorian and Edwardian artworld, yet I am certain, almost to the point of offering a ruinous wager, that most readers will not come up with the name.

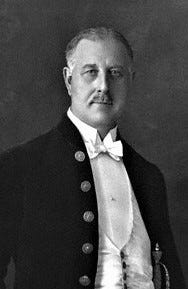

So let’s try - his name is Richard Jack, RA (1866 - 1952). You see, I’m right. His name never occurred to you. You have probably never heard of him.

Richard Jack’s achievements were not just significant enough to raise him well above most of his peers practising between the 1890s and 1930s, they were quite extraordinary by any standard. Yet, if you want to see some of Jack’s work today, you’ll have a bit of a job. Some does hang in decent collections, like the superb York Art Gallery for instance, but that’s no surprise since he was an adopted son of York - studying at the City’s art school and scooping all its main prizes before moving on to study in Paris. It would be shameful if they didn’t have at least one significant work.

There are also several Jacks in the Royal Collection – the world’s largest “private” art collection where his paintings sit amongst 7,000 other oils, plus 30,000 watercolours and 150,000 works on paper. They are housed in 13 Royal residences and voluminous archive stores. Your chances of seeing one of their Richard Jacks is slim. You might spot his signature in several regional galleries, where there could be a formal portrait of some mutton-chopped dignitary from Jack’s time as a journeyman portraitist. They can be found in places like Wakefield, Hartlepool, Sunderland – and many similarly faded municipalities which have now been emasculated by local Government “reforms”.

All in all, he’s pretty much forgotten today.

My own awareness of Jack began when I was on the Board of York Museums Trust which includes the city’s Art Gallery. When attending Trust meetings I would pop in to see his painting “Return to the Front” which hangs in one of the main galleries, with a handy bench opposite providing the perfect opportunity to really study Jack’s painting and his technique. (A quick aside: Why are there so FEW seats in most art galleries? I will return to this issue in a future post)

“Return to the Front” is a super painting, in my view, and it stayed in my memory for years after I left the Trust. It’s not a record of a single event, but a fictional composite, paying tribute to the troops who crowded Victoria Station between 1914-18, making their way back to the horrors of France after a brief furlough. The desolate Scots soldier in the front of the painting tells, for me, of the silent misery of men who not only know what fate awaits them - but are also keenly aware of everything they are leaving behind. A return to the front must surely have been far worse than the first time they were shipped to France. There may be the noise of steam trains, station announcers and the cries of vendors, but each of these men are alone in their thoughts and worries. Enquiring about the painter I was intrigued to discover that Jack was an official war artist in World War One –though he worked for the Canadians and not the British – so I did a little reading on the subject of war artists and then put the subject aside.

This brief study was to prove very useful a few years later when I started an MA in History of Art. One of the requirements was a substantial dissertation on a subject which would require significant research and make some original contribution to the sum of art history knowledge.

That’s trickier than it sounds – but I thought I had a cunning plan. I was planning to study an obscure woman artist whose work I collect and about whom I already knew quite a lot - Nelly Erichsen. (If you don’t know of Nelly, my wife Sarah later wrote an excellent biography of her entitled Nelly Erichsen - A Hidden Life. The Kindle version is available on Amazon) .

When I took this idea to the course tutors at the University of Buckingham, they turned it down flat. Possibly they felt I had created an unfair advantage for myself by having already done a lot of the groundwork. But it did leave me with an urgent need for another subject - something interesting enough to inspire me through the low points of a two year project, yet which also offered plenty of archive material which might yield the original research required. In a bit of a panic - and thinking of that Jack painting in York - I proposed to research the origin of “official” war artists, knowing that I at least had somewhere to start with Richard Jack. It proved a lucky choice. The subject was everything I needed and I also managed a Distinction in my MA.

However, it’s Jack we’re interested in here. So take a little break from reading this and look at this interesting video on “Return to the Front” presented by the curator at York. You’ll find it here https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=richard+jack+return+to+the+front

Born in Sunderland in 1866, there was little in Jack's family background to suggest the talent and career which was to unfold. Yet by the time he was studying art at York, it was clear he had huge potential. He came first in every one of his art disciplines and two of his works were put forward for a national competition which resulted in a national scholarship to the Schools of Art in South Kensington.

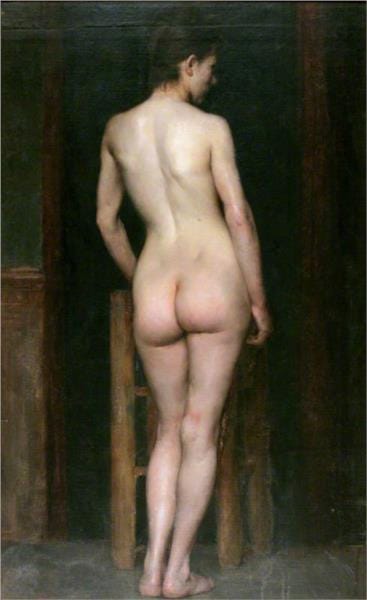

There he won the gold medal for drawing from life – “his execution is facile, the flesh tones, modelling and pose being rendered with truth to nature,” said the judges. He also won a travelling scholarship which took him to Paris for the first of two spells at the famed Academie Julian. There, again, he was a medallist (1890)

After the successes and the glamour of student life in Paris, Richard Jack went back to living with his parents in the modest terraced streets of Bootham, a working class district of York. It could have dulled the ambitions of a less determined man, but Richard Jack always had a considerable work ethic and he kept his feet on the ground. He married his fiancée, Rebecca, and while some artists toiled in poverty to hone their skills and hope for recognition Jack - maybe influenced by his father’s life as a print worker - got himself a job as an illustrator in magazine and book publishing. By day he produced a flood of black and white illustrations for the Idler magazine, quickly becoming the preferred artist to bring to life their long-running serials. He appears regularly in the credits column of the magazine until well into 1895, during which time he and Rebecca had moved to London and started a family. In his evenings and weekends, he plugged away doggedly at securing portrait commissions and producing saleable miniature paintings, which were a popular Victorian artform.

In 1893 he secured his first two hangings at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, one of which, “Everilda”, was favourably mentioned in newspaper reviews. These days the RA Summer Exhibition is still a significant event in the art calendar but in the 1890s, blessed with heavy Royal patronage, it was an enormous enterprise. Today around 100,000 people tour the RA’s Summer Exhibition. Back then up to 400,000 pressed into the Academy’s galleries. The art magazines produced special editions and even the regular dailies and weeklies devoted many columns to exhibition reviews. Commercial printers bought reproduction rights to the most popular works and editions of several hundred sold well to the growing middle class market. Good reviews also secured a strong flow of future commissions.

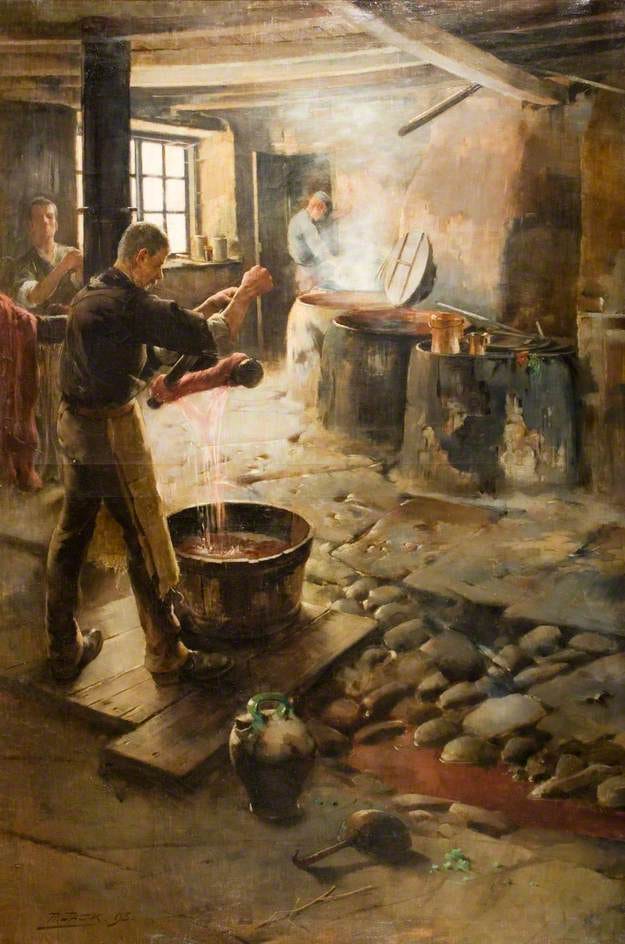

Richard Jack made his main income from portraits but he was keen to be recognised for more academic work. In the 1890s he submitted a stream of work with classical themes such as “The Remorse of Cain”, “Cleopatra” and “Reverie” to the Royal Academy. He also produced some excellent documentary works - well-reviewed was “The Swedish Dyehouse”, acquired by enthusiastic donors from Leek, Staffordshire for their local town hall. (Swedish refers to a dyeing technique which was widely deployed in the Northern textile industry, not the nation).

Ambitious for further acclaim - and probably with a keen eye on the financial outcome - Jack chased valuable art prizes. In 1914 his oil “The String Quartette” was sent to Pittsburg, USA, as one of 340 entries from international artists for the annual Carnegie Institute medal. Jack came second and collected $1,000 - around £30,000 in today’s money. Just as important was the coverage in the art press in America and at home. The work was bought by a Northern municipal gallery and last seen at Sothebys in 2018 where it sold for £18,750.

Successful portraitists enjoyed excellent incomes in Edwardian times - and Jack developed a strong reputation. He and Rebecca moved to fashionable Elm Bank Gardens, Barnes, a boom area for developers who threw up impressive mansion flats and fine villas along the Thames. By now they had two children - a boy and a girl - and required servants. There is good evidence he was in the front rank of London studios. Already elected a member of the Society of Portrait Artists before the turn of the century, Jack was one of a leading group of Society portraitists who broke away and created the National Portrait Society in 1909, pretty much a trade body promoting the most admired - and highest paid - practitioners. Jack was a founder, along with John Lavery, William Orpen, John Singer Sargent, William Rothenstein, Francis Dodd and others. It was clearly a strongly commercial project. The Manchester Guardian reported the new breakaway group were unhappy with the existing societies “which were severely handicapped by including in their midst an unduly large proportion of painters of moderate talent”.

So far as I know, it is not possible to establish Jack’s exact output between the start of his career and the outbreak of WW1. I have not had access to his studio workbook or any personal papers and have not managed to find any of his decendants who have those records. But from studying the catalogues which are available in the Academy archives, we know he had well over 50 successful submissions to the RA Exhibition in a 15 year period. His studio was very well established by 1914, and that year he was elected ARA by the Academy. As is traditional, his “Rehearsal with Nikish” was acquired by the Trustees of the Chantry Bequest and is now in the possession of Tate Britain.

The Edwardian years were profitable for Richard Jack. He found his clients among the newly rich, whose profits from the industrial boom enabled them to immortalise themselves and their families in portraits. It was not only individuals who commissioned portraits - learned Societies, newly prosperous cities and thriving businesses, too, wanted to honour their Presidents, Mayors and Chairmen with portraits. Jack was in demand - not only for his artistic output. He became a familiar face at London social events, often contributing to charitable fund-raisers for benevolent causes. He was good humoured and out-going - an ideal MC for a charity evening. Music was a great interest of his - as can be seen from the subjects of his non-portrait output. But he also had a fancy for himself as singer and I have found several press cuttings which mention his performances.

Truly it was a glorious era - but as we know, the glamour of the early years of the 20th century was to come to a ghastly end with the 1914-18 War. For Jack, however, a new career opportunity dawned which would propel his name to prominence internationally as well as in England.

The art of war

Art and war were far from strangers as the 19th century turned into the 20th. There had long been a symbiotic relationship between the British military and the artists who portrayed them, as a result of which military commissions had become one of art’s major economic engines. The Dictionary of British Military Painters lists more than 400 painters who were active between 1750 and the early years of the 20th century commissioned by the victorious to create stirring images of great battles, of heroism and of the regiments and their generals. Yet Europe’s Great War of 1914-18 disrupted this profitable relationship as fundamentally as it changed so much else in the military and the civilian worlds.

The catalyst for this change was the phenomenon of the Official War Artist, sponsored and assisted by Government, which had its genesis in a secret propaganda initiative by the British Government and its later development in the ambitions of a colonial media magnate who came to Britain seeking power and influence. The coming together of these unlikely bedfellows during WWI produced what the critic and curator Frank Rutter (1876-1937) called “the greatest ever act of State patronage of the arts in Britain” and created a genre of documentary art which continues to record the lives of fighting men and women to this day.

World War I was a conflict which began on horseback and went on to witness the beginnings of “Techno-war” - high-tech, capital-intensive warfare fought by machines as well as men, with the ruthlessness and efficiency of the production-line. The old order of battle painting was cast aside, along with the cavalry charge and the cutlass. Famous artists whom the British public associated with military art prior to 1914 were refused all access to the fighting. Instead, a cadre of younger men, many recently out the country’s most advanced art school and who had never experienced war, were selected by the propagandist unit to don khaki and paint at the Front.

For the first 15 months of fighting, at the personal insistence of Britain’s Secretary for War, Field Marshall Lord Kitchener, journalists and artists were kept away from the Front by a nervous alliance of politicians and generals. The fighting was shrouded in what Winston Churchill famously called “the fog of war”. Art did play some part on the Home Front where the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee, founded in August 1914 as a cross-party organisation, commissioned more than 100 poster designs to boost public support for war and more than 2,500,000 copies were distributed. Works such as Remember Belgium by Frank Brangwyn (1867-1956) became ubiquitous on underground trains and poster sites.

Eventually, a secretive Government propaganda unit proposed sending a couple of artists (given commissions in the Army Service Corps and thus able to wear uniform) to the Front in order to provide graphic illustrations of the deprivations being inflicted on French cities by the German bombardments. Artists rather than photographers were chosen as the results from early photography were simply not dramatic enough. Their work would be used to justify Britain's involvement in the conflict to families at home, whose sons were off fighting, and also to try to persuade a reluctant American public the USA should join the war.

The first official war artist was Muirhead Bone (1876-1953) a talented illustrator whose vivid black and white etchings of devastated French cities created a significant impact. Within a few weeks Francis Dodd (1874-1949) Bone’s friend and brother in law, was sent on the same mission.

Then newspaper publisher Sir Max Aitken (1879-1964) spotted the new propaganda images and was impressed by both their impact and the public reaction to exhibitions of the work. A Canadian business magnate, who had moved to London seeking influence at the heart of the Empire, Sir Max realised the power of these contemporary war images and proposed that he fund a war art programme for the Ottawa Government, but with a rather different emphasis. Canada - still a Dominion of the British Empire, rather than an independent nation - was supplying huge numbers of soldiers and equipment for the war and Aitken (later enobled as Lord Beaverbrook) wanted to record and glorify the efforts of his countrymen.

After the first Battle of Ypres in 1915, which saw more than 6,000 Canadian casualties, Aitken had persuaded the Canadian Premier, Robert Borden to let him establish the Canadian War Records Office, headquartered in offices paid for by himself, at 3 Lombard Street, in the City of London. The CRWO ( led by Aitken, commissioned as a Lt-Colonel in the Canadian army plus 11 officers and 17 other ranks), was the result. He wanted dramatic, enduring images of the Canadians at war and commissioned top rank artists to immortalise Canada’s contribution to the war effort. His adviser on potential artists was Paul Konody (1872-1933), editor of an English art magazine and for many years art critic of the Observer and Daily Mail newspapers. As a result the CRWO relied heavily on British artists. These eventually included Augustus John (1878-1961) and AJ Munnings (1878-1959) - but the very first was Richard Jack.

The result of Jack's recruitment - now in Canadian army uniform and wearing a Major's insignia - was epic canvases, including The Second Battle of Ypres, and The Taking of Vimy Ridge, which were widely admired in Canada. They can be seen to this day in the Canada War Memorial in Ottawa. And the work made Jack a public figure on both sides of the Atlantic.

Other artists who joined the Official War Artist programmes of Britain, Canada, Australia and the USA are widely known and talked of to this day. Yet while Richard Jack was both a pioneer in the field and widely recognised at the time, he is not. Certainly Jack went on to achieve greater distinction and significant income from his post war work. He was a favourite portraitist of King George V and Queen Mary and his reputation kept his name in the newspapers and society magazines well in to the 1930s. In my next Substack I will continue his story…..

The nude painting is wonderful