How three French girls, holding bouquets, stood their ground against Nazi troops

Quiet defiance by an entire French village means the last resting place of a lost RAF crew is not forgotten 80 years later

This month much of the free world will be remembering the millions who died in two World Wars in countless ceremonies, large and small. It is hard to give a human face to the staggering statistics of deaths in combat, but the story behind of seven Portland headstones in a tiny French village is a particularly poignant reminder that behind each hard statistic is a personal story.

Search for La Bussière-sur-Ouche on an electronic map and you have to zoom pretty deep into the wooded hills, west of Nuits-Saint-Georges, to pick out the handful of houses, surrounding the old Abbaye de la Bussiere, which forms this forested commune. Just a little up the hill from the Abbaye - now a magnificent chateau hotel - the seven white headstones stand in an immaculately-tended, gravel plot .

I came across the graves, just over the road from the village church, on an evening stroll while Sarah and I were staying at the former convent, which dominates what is little more than a hamlet. It’s a lovely hotel, with excellent food and some striking sculptures by the English artist Paul Day - he of the “Lovers” statue in St Pancras Station and the Battle of Britain Memorial. It was a beautiful evening - a time when you felt all was well with the world. I was rather unprepared, therefore, to come across the seven headstones in their well tended plot, as Commonwealth War Grave Commission memorials always are. There were photographs, faded poppies and even a vintage tin of “Anzac” biscuits laid in tribute beside the stones - clearly mementos of visits by people who had a connection with the airmen who died 80 years earlier.

Curious about the biscuit tin, I looked closer at the inscriptions on the stones - and I could see that two of the dead were from the Royal New Zealand Air Force, their engraved badges bearing the Maori silver fern symbol, set in a Celtic cross. Another of the seven graves was that of an Australian pilot, who I later discovered had developed his flying skills in an old Tiger Moth at a remote airfield in the centre of New South Wales. The other four - one a teenager - were English. I was moved by the fact that none of these young flyers had any connection with France, maybe had never even seen the country, except from thousands of feet, on their moonlit flight to cross the Alps into Italy, and yet their graves seemed to mean so much the locals at La Bussière.

It is an inevitable result of world war that young men fight - and die - far from home. But how did they come to rest here and why is their memory apparently so special to these French villagers, I wondered as we walked back to the hotel.

The story I learned back at the hotel and subsequently embellished for myself from web-based records, was one of courage and humanity by French civilians, who faced-off their Nazi occupiers to ensure a decent burial and a lasting memorial for seven young strangers.

There had been nothing they could do for the airmen when the burned-out wreckage of their plane was found at dawn on August 13, 1943. It wasn’t even possible to properly identity each of the casualties. But the villagers reverently collected their remains, took them down the hillside and subsequently - in defiance of instructions from the Germans - mounted a full burial service. They collect rank badges, scraps of paper, cigarette cases - anything which could identify the dead men. These were later handed to the Red Cross and enabled family and RAF authorities to know their fate.

The final flight of EF390 had started only a few hours earlier, when the lumbering, four-engined Stirling bomber had taken off from RAF Chedburgh, Suffolk, bound for Turin - one of many aircraft aiming to bomb munition factories. As usual on these multi-bomber raids, where aircraft from up to a dozen RAF stations departed in a short space of time, there was a long queue of planes waiting their turn on to take off. A Canadian pilot, Murray Peden, who served at Chedburgh during 1943, recalled in his memoirs how villagers would gather outside the Marquis of Cornwallis pub, just 100 yards from the perimeter track “for their nightly show”. It must have been a noisy spectacle, with each Stirling having 4 huge Bristol radial engines together putting out a total of 6,600 horse power, but it would have still been light enough to clearly watch EF390 as its wheels left the runway at precisely 21.35.

Operation Turin of 12/13 August 1943 aimed to “area bomb” the industrial sector of Turin and a total of 152 aircraft left England that evening, intending to link up over the target area, with a special focus on the vast Fiat works at Lingotto - an iconic building with an extraordinary 1.5 kilometer oval test track on its roof. It was not expected that many civilians would be at risk, as 465,000 people had already left the city, driven from their homes by previous bombing raids. Indeed, only 18 people were killed on the ground and 63 injured. The toll on the RAF was also comparatively light. 142 aircraft made it home on the morning of the 13th.

The fate of EF390 was tragically different. Damaged, presumably by anti-aircraft fire, she became separated from the rest of the RAF Chedburgh group, but was still aiming to limp home safely and was over half way home when picked up by a German radar station at Saint Jean de Boeuf close by La Bussière. Stirling bombers were often criticised for their comparatively low operational ceiling, which made them more vulnerable than high-flying rivals. Damaged as it was, EF390 was probably flying even slower and lower than its Australian pilot, Fred Matthews, would have wanted - but with good luck he probably thought he could make it back.

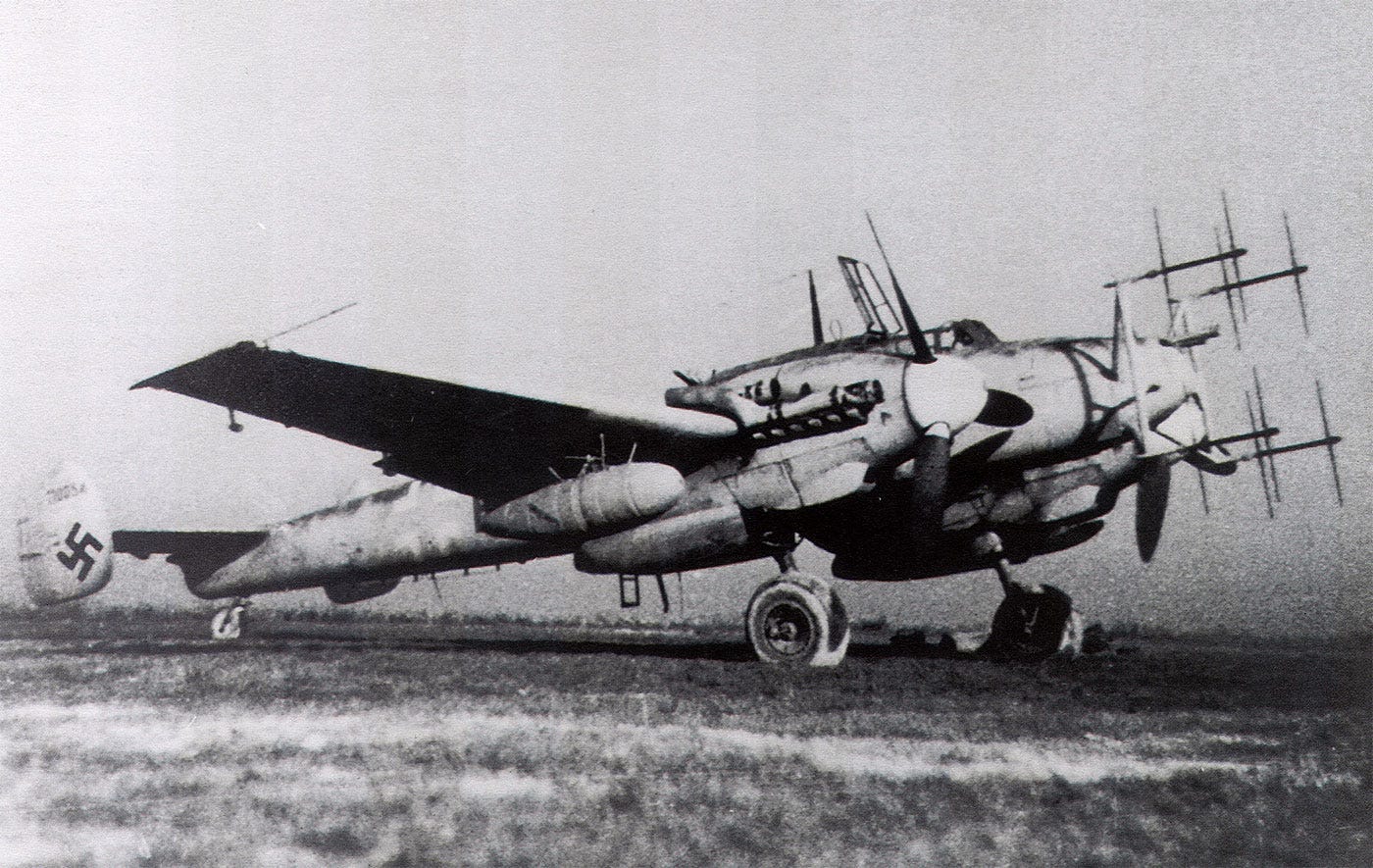

That was not to be. The first stroke of bad luck for the crew of EF390 was that the Dijon area had been chosen as the site for particularly sophisticated German radar apparatus. When Allied aircraft were spotted, night-fighters were scrambled and sent in pursuit. Unhappily the Dijon military airfield (today the civilian Aéroport Dijon-Bourgogne) from which German fighters operated was home to a unit of Germany’s II/NJG (Nachtjagdgeschwader) night fighter wing, equipped with twin-engined Messerschmitt BF110s. These ungainly-looking planes were made to look even more peculiar as they carried an early radar of their own in order to home in on the target aircraft. This radar looked rather Heath Robinson, with a cage-like device mounted on the front, but it was effective and that was the second piece of bad luck for the Allied crew.

The third was that a particularly skilled and daring officer, Hauptmann (equivalent to Flight Lieutenant ) Hans Wolfgang von Niebelschütz, with nine “kills” to his name, was on duty at Dijon when the scramble alert sounded. He had to take off and cover just 25 kilometers from his base before he came upon the stricken Stirling. He positioned his aircraft behind and below the bomber - where the crew could not easily see him. Messerschmitts like this were heavier and less manoeuvrable than the nimble day-fighters used in aerial dog-fights, but thanks to their twin-engines and bulky airframe they could carry much heavier machine guns. And to make the tactic of sneaking from behind and below their victims even more lethal, these night-fighters had upward-facing guns which could be aimed right into the belly of the target plane.

Probably the first that Fred Matthews and his crew knew about the attack was when von Niebelschütz’s initial blast ripped into the bomber’s fuselage and they were sent spiralling down in flames, into the forest.

There was no hope of survival. The Allied airmen died at 2.42 in the morning, some of them before the aircraft hit the ground and exploded, as bullet wounds were found in some bodies.

Horrific though it is, the story of EF390 is far from unusual. Small groups of Allied graves can be found across France, Belgium, Holland and Germany. Life in Bomber Command was brutal and could be very brief. It was one of the riskiest postings of any Allied forces in WW2 - with 55,573 personnel out of 125,000 dying in action, with more than 8,000 wounded and almost 10,000 becoming prisoners of war. The risk of flying Stirlings were even greater - within five months of the type being introduced, 67 out of 84 aircraft had been lost to enemy action or written off after crashes

It is not just the sad fate of the airmen which I found so particularly sad when I heard the story, rather I was very moved when I heard the reaction of the French villagers.

That morning the authorities turned out the local fire brigade to locate the crash. The pompiers were soon joined by other villages and all morning they worked to recover the badly mutilated bodies and try to identify the airmen. German soldiers also arrived but they were more interested in what intelligence the wreckage could provide. It took more than 24 hours to complete the gruesome task of locating what remains they could before the pompiers brought the seven bodies down to La Bussière. The recovery team were particularly appalled when they were interrupted in their work by the arrival of a Luftwaffe officer, in glamorous ceremonial uniform. This was von Niebelschütz himself, the pilot who shot down the bomber and the villagers noted his “scorned, haughty, arrogant demeanour”, as he strode around the site looking at his handiwork, according to contemporary reports.

Down in La Bussière the next day the bodies were taken to the Town Hall and placed in seven coffins, while the Commune arranged the burial. There they were visited by German soldiers who warned against any large gathering or ceremony during the interment and warned they would be back for the funeral.

The villagers had other ideas. By 5 pm the next day a large crowd had gathered at the Town Hall. Reports say “in spite of protest from German troops the coffins were under hundreds of flowers, bouquets and four beautiful wreaths, one of which was from local veterans”.

At the gravesite the small troop of Germans again tried to prevent the crowd taking part in a ceremony but they were overwhelmed by numbers and caution reigned. In front of the graves three young village girls stood holding flowers and facing the troops - one dressed in red, one in white and one in blue, the colours of France and also of Britain

Finally, in the face of such bravado and compassion the German soldiers relented. As the burial went ahead they simply presented arms and bowed their heads.

Eighty years on from that brave display by villagers - who were captives in their own country and had nothing to gain from their honouring of seven young men with whom they had no connection - visitors to La Bussière-sur-Ouche can still take a moment to reflect on a generation whose sacrifices brought freedom to Europe and much of the rest of the world.

I am acutely aware that I am part of a golden generation. We grew up in the first era for more than a century when young people did not face a demand for any military service. It seems to me that if sacrifice was the price demanded of those seven young men and millions of others 80 years ago in a fight for our future, then remembrance is the least we can offer in return.

It’s a lesson which the villagers of La Bussière-sur-Ouche still teach us every year in an annual ceremony as relevant in 2023 as it was in 1943.

I wrote this Substack in gratitude for all of my father’s generation who gave so much to make life safe, free and prosperous for mine, exemplified, particularly, by the crew of Stirling bomber EF390:-

Pilot Officer Frederick George Matthews, Pilot of EF390, Royal Australian Air Force, aged 25. Son of Jewell and Lydia Jane Matthews, of Yanco, New South Wales, Australia. His headstone bears the inscription "Safe With The Lord"

Flight Sergeant Albert Douglas Harris , Air Gunner, Royal New Zealand Air Force aged 23. Son of Frederick John Linton Harris and Amelia Rose Harris, of Huntly, Auckland, New Zealand.

Sergeant Henry George Ott, Air Gunner Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, aged 19. Son of Henry George and Florence Ada Ott, of Woolwich, London. His headstone bears the inscription "We Miss His Smile, So Good, So Kind. A Beautiful Memory Left Behind"

Flight Sergeant, Alistair Frederick Rose, Navigator, Royal New Zealand Air Force, aged 20. Son of Alexander Frederick and Mary Rose

Sergeant Kenneth James Cork, Wireless Operator, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, aged 21. Son of James F. Cork and Florence Cork, of Norwich; husband of Elsie Maud Cork, of Norwich. His headstone bears the inscription "We Cannot With Our Loved One Be, But Trust Him, Father, Unto Thee"

Flying Officer Frank Wilfred Holland, Air Bomber, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, aged 32. Son of Frank and Emma Holland, of Brighton, Sussex. His headstone bears the inscription "He Never Knew Fear"

Sergeant John Geoffrey Knight, Flight Engineer, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, aged 27. Son of Joseph and Violet Knight, of Birmingham. His headstone bears the inscription "At The Going Down Of The Sun And In The Morning We Will Remember Them"

Footnote:

French accounts of this incident report that Hans-Wolfgang Kurt Balthasar von Niebelschütz, who was 29 when he shot down the Stirling, was later shot down himself over France and although not killed “He was treated badly, beaten and stripped of his personal belongings by the villagers.” Whether or not this is true, Niebelschütz did not survive the War. Official records show he died in January 1944, ironically by the action of his own side. Anti-aircraft fire hit his aircraft at Engelsdorf near Leipzig and despite baling out, he died.

Sadly I don't - but they would be 90 odd by now if they are still alive. It's not likely many people from that crowd would still be alive, but I bet some are.

Very moved. Me also of the golden generation. Am sending to a number of friends of the same generation, who will immediately understand. Thank you and well done.