Nude sunbathing on the church roof...

The closure of a famous magazine reminds me of the eccentricities of its writers

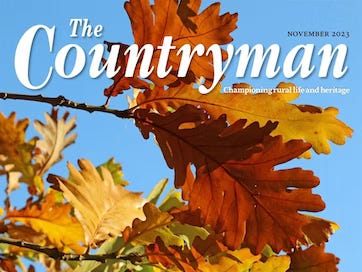

Just short of the centenary of its founding, the November issue of the Countryman magazine will be its last.

Battered by rising costs of those crucial 3 P’s of publishing - paper, printing and postage - the latest owners of the cult magazine for townsfolk who dream of the countryside, have decided it is no longer viable. The last copies will soon be dropping through subscriber letter boxes.

The chances are you may never heard of the Countryman, let alone thumbed through one of its stubby A4 issues, devouring the articles on our disappearing past. At its height around 90,000 subscribers awaited each quarterly report from the rural front line. A constant lament of the Countryman, from the day of its foundation, was that everything we know and love, outside of the warm glow of urban Britain, is disappearing. Country crafts were always under threat, badgers were a constant concern, rural skills had all but died out. It’s more than a little ironic that the magazine which championed them should have pre-deceased them all.

Lately, though numbers are not available, it is believed that only a few thousand of the iconic, green-bordered magazine made it into readers’ hands.

The Countryman was quirky, nostalgic and occasionally campaigning - and it was in the vanguard of many important ecological issues. (I spotted an article on “re-wilding” in a decades-old edition). Yet the tale behind the magazine itself is just as fascinating as any of its cover stories - so we’ll move on to the nude on the church tower in my unashamed, click-bait headline for this article.

Our naked sunbather didn’t just catch your eye, she was a minor hazard for air traffic at the newly opened RAF Rissington on the Oxfordshire-Gloucestershire back in 1938. The pre-war skies, above the remote farming hamlets, were full of eager young pilots doing their circuits and bumps in the rather primitive, open-top Avro Tutor aircraft available to them then. As they came round for their final approach the young aviators would line up on the stout little church tower of St. Nicholas in Idbury - and below them they often saw young Joyce Westrup stretched out on her towel, naked as a cherub.

Joyce was one of the young writers, advertising staff and circulation clerks who were enticed to Idbury by the Countryman’s eccentric founder/Editor, who had his home and his office in a three-storey Manor House on a small promontory at the heart of the hamlet. Even now there’s not much to Idbury, just a few cottages and a couple of farm houses, huddled together between Burford and Bourton-on-the-Water. Today those are two of the most crowded tourist villages in the Cotswolds, but not more than a handful of tourists find their way to Idbury.

For J W Robertson Scott, founder and owner of the Countryman, the isolation was clearly key to his business model. Save for the enterprising Joyce, his staff found little else to do when marooned at Idbury, except apply themselves to writing and selling the magazine. Scott was a tough employer, although he imagined himself to be a benevolent father figure. Victor Bonham-Carter, employed as a Countryman writer, recalls in a memoir that Scott “was a monster. He attracted young people into the country, eager to work for an “idealist” enterprise, willing to learn and willing to work for next to nothing while learning; but when they became useful, deserving proper pay, he sacked them and recruited fresh fools in their place.”

Bonham-Carter, later a prolific author on rural matters and secretary of the Society of Authors, eventually tried to exact revenge on Robertson Scott by launching a rival to the Countryman. Along with another ex-staff member, Frank Prewett, a Canadian who had a reputation as an excellent poet, he left and founded Country Scene and Topic. They set up in Bourton-on-the-Water, but it was not a success, even though there was a decent population locally of disaffected Countryman staffers who had walked out on Robertson Scott during one of his rages. Prewett was a classic example of the talent which Scott lost through his appalling behaviour. He was a friend of Siegfried Sassoon (they met at the military recuperation hospital at Lennel House in the Cheviots) and his poetry was collected and edited by Robert Graves in a posthumous edition in 1964.

Things were so bad at Idbury, according to one former colleague who wrote to Bonham-Carter: “Eight of the staff went in six months. Four were sacked and four gave in their notices. The Editor had me in and said that I had dared to go on associating with a member of the staff who had been sacked and that I had let him down badly. Was I in future prepared to give him my utterly loyal support in everything I did? I said I valued my liberty too much to promise anything so rash, but pointed out that my work had always been well and conscientiously done. He said, ‘I am not talking about your work’ and then told me I had best resign.”

Even for those who stayed, life was spartan and ill-paid. Most had lodgings with farm labourer families in damp and draughty tied cottages. They soon found that Robertson Scott’s rural idyll, espoused by the magazine, wasn’t so cosy in reality!

Scott’s own back story is itself a pretty good yarn. Born in the 1880s, he had a distinguished career, first at the Birmingham Gazette and later in Fleet Street. But he was a man of resolute principles, which often led him into conflict with colleagues or the management. He finally quit newspapers because his then employers, the Daily Chronicle, supported the Boer War. Scott decamped to rural Essex where he freelanced as a writer on rural affairs, particularly campaigning on the decline of traditional farming. One of his books sums up his key theme - The Dying Peasant and the Future of His Sons.

Scott was a vegetarian, pacifist and teetotaller and didn’t flinch in pursuit of his causes. During WW1, too old to be called up and therefore unable to take a stand as a conscientious objector, he instead moved to Japan with his wife and studied that country for six years, producing endless articles and even a magazine for Japanophiles.

In 1923 he moved to Idbury - and in 1927 began the project for which he best-known.

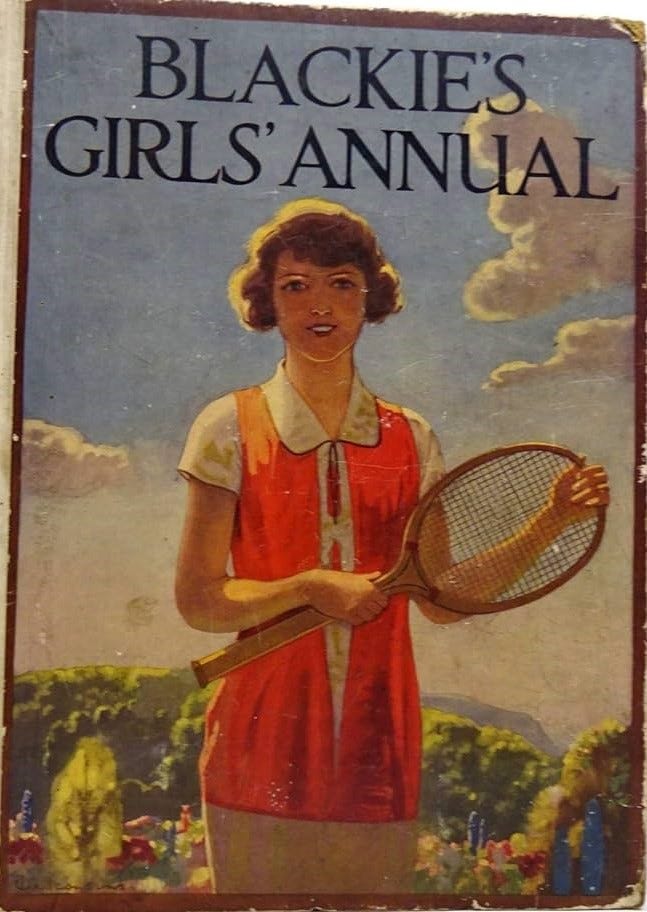

Many of those who slaved away for Scott went on to successful careers elsewhere. Joyce the sunbather became a successful writer of children’s books, producing Blackie’s Girls’ Annual and other books. She married another Countryman staffer, David Green who wrote an entertaining account of life under Scott in an autobiographical book Country Neighbours. Green left Idbury to work for Punch and later became archivist at Blenheim Palace.

It has to be said that Scott led from the front when it came to hard work and long hours. He and his wife Elspet were they entire staff of the magazine for its first couple of years and Scott was a persistent salesman. He is said to have taken copies to every advertising agent in Fleet Street, leaving them at reception along with a punnet of strawberries. The following week he re-traced his route and collected a decent number of advertising orders from the intrigued agencies.

Whatever his reputation among his staff, Scott seemed to find no difficulty persuading famous names to contribute, a tradition which continued long after his ownership. Prince Philip wrote a long lament on Dutch elm disease in 1977. I spotted other pieces by Spike Milligan, Magnus Magnusson, Alan Coren and Chapman Pincher as I browsed past copies offered for sale on the web.

Yet the core of the product was always obscure rural traditions, treks through “lost” landscapes and cheery articles on the cuter fauna of Britain, to which the writers often gave alliterative names….Brock the Badger and Wally the Weasel are two which jump out of contents pages.

Scott eventually sold the title in 1943, to the owners of Punch magazine and operations moved to the bucolic-sounding Sheep Street, in Burford, although Scott continued as editor for a further four years. The magazine has changed hands a couple of times since, most recently to the publishers of the equally singular Dalesman magazine.

It is in their hands that it has finally ground to a halt, burdened with costs which can’t be recovered from subscriptions and advertising. I don’t blame them in the least - I have flogged one or two dead horses myself in my lifetime in publishing. It is always difficult to know when to administer the coup de grace to a product which is in decline, but still adored by its core audience.

Looking at the 97 years of the Countryman I can’t help thinking that maybe Scott, his magazine and his largely urban readership were part of their own downfall. By weaving a romantic, nostalgic picture of rural life, folk like Scott simply hasten the death of the countryside they love. The more appealing they make it - the more townsfolk want a piece of it. You won’t find draughty farm houses and cottages with rat-infested thatches in today’s Cotswolds. Homes round Idbury which the Countryman staff rented for £5 a year are now listed by estate agents for millions. The owners don’t need to subscribe to Scott’s dream world - they’re living it, or least a rather glamourous version.

Today there is little reason to visit Idbury, save for a peep at the parish church of St Nicholas (no access to the tower for sun-bathing these days, I suspect). The busiest part of the day is probably when the commuters, who bought up all the farms and cottages in the area, make their dash for the London train at Kingham. For them the hamlet is just a tricky chicane on the back-road between Nether Westcote and Foscot - hamlets where Scott’s staff found dingey digs back in the 1930s. But if you do glance up as you approach the blind bend on Church Street, the 3-storey stone building directly ahead is Scott’s old home.

A while ago builders’ lorries were parked there for several months, so I imagine today’s occupants of the old house no longer suffer the privations of Scott’s regime.

If you want more first-hand yarns of life in Scott’s singular management style and life in his Countryman commune, then there is a lot more in Victor Bonham-Carter’s autobiography - What Countryman, Sir? It was privately published, so hard to find. David Green’s Country Neighbours is quite easily found second-hand.

The Dalesman is still going strong - and with a digital edition -https://www.dalesman.co.uk/

Fascinating! I admire anyone’s ability to create a successful publication, but I hate learning the horrific accounts of what’s now called HR.

Always sad to see a print magazine go.

Lovely article. I once stayed at an excellent B&B in Nether Westcote. Irrelevant, but a very happy memory ☺️