Dante Gabriel Rossetti has never been my favourite pre-Raphaelite. For me, his work has neither the vivid realism of Holman Hunt nor the extraordinary draughtsmanship and story-telling of Millais. There is no doubt, however, that he and his siblings made a significant contribution to Victorian art and literature – and are people about whom I should know more than I do.

A visit last week to “The Rossettis” at Tate Britain was therefore a fine solution to a wet London day.

The Tate has had a bashing since its much-heralded “re-hang”, but this exhibition is immersive, instructive and enjoyable.

DGR probably gets a worse Press than he deserves, but he brought it on himself through his prickly character and his cuckolding of his pal, William Morris, whose wife Jane was DGR’s mistress for 20 odd years.

The exhibition is well worth a visit for anyone interested in the talented Rossetti family and their extraordinary output. And it inspired me to read more about Rossetti – specifically to dig out a small green volume of biography that has been sitting on my “Art books I must read…” shelf for years, among several dozen volumes I bought as a job lot, when I was studying for an MA in the History of Art.

The author, Joseph Knight, an art critic and friend of Rossetti, was writing just five years after DGR expired on Easter Day 1882 (during a convalescent trip to Birchington-on-Sea in Kent). His appraisal of Rossetti is understandably warm and largely uncritical. Yet it is a source of insights and yarns as well as a skeleton account of his career

.

I like, particularly, his telling of behind-the-scenes life at DGR’s impressive final home besides the Thames on Chelsea’s Cheyne Walk. It was the venue for many “brilliant and interesting” gatherings, says Knight. DGR took the house with his brother William and the poet Algernon Swinburne after the death of his wife and muse, Lizzie Siddall. He lived there for the rest of his life.

It was not just a home, but a club for DGR’s glittering group of friends. Rossetti enjoyed showing off his home and made the garden a shrine to his vision of nature and wildlife. He also established an eccentric menagerie at No 16, including peacocks, armadillos, parrots, a Japanese salamander, a wombat, a raven and various owls.

The most outrageous and unsuitable of these pets – considering the confines in which they had to be kept – was a Zebu bull, a type of cattle originating in India.

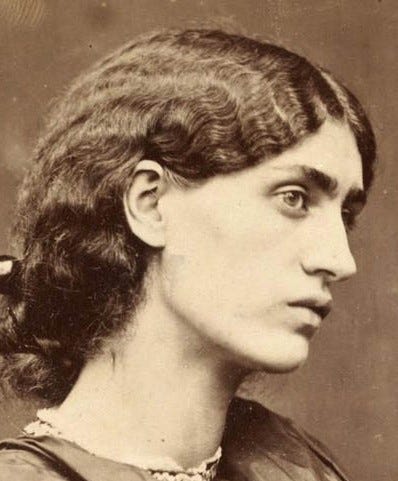

Zebus have a long face with a lugubrious countenance – not unlike many models in pre-Raphaelite paintings. Certainly Rossetti felt so. The animal’s eyes reminded him of those of his lover Jane Morris and, greatly struck by the beast’s mournful beauty, he persuaded his brother William, with whom he shared the house, to go halves on the £20 purchase.

16 Cheyne Walk had seen an astonishing variety of wildlife since DGR’s arrival, but installing the Zebu presented unique challenges. The house (you can see it to this day, with a blue plaque on its facade, just downstream of the Albert Bridge on the North embankment) was spacious, but terraced and the only way to get the bull into the back garden was through the house. It was not a straight route, either. The passages were, remembers Rossetti’s biographer, tortuous and of no great width. Here the scheme ran up against another of Rossetti’s passions – his large, fine collection of blue china which occupied the shelves and cabinets in corridors through which the unfortunate bull had to be taken.

“A veritable bull in a china shop,” says Knight so the Zebu had “with the greatest care, to be carried, firmly bound and lassoed, into its destined home”.

The problems were not over, as the Zebu was fierce and grumpy which left the brothers with no choice but to leave it tied to a tree in the centre of the garden, for safety. The animal was regularly displayed to visitors, with Rossetti keeping his distance and pointing out the animal’s attractions with a stick. But the Zebu eventually developed a smouldering resentment towards its captor.

Knight completes the story thus:-

“The fierce little animal, which was not much bigger than a Shetland pony, nursed a sullen resentment against the indignities to which he was subjected. One day, when the two were alone in the garden and Rossetti was contemplating once more his admired possession, resentment blazed into indignation.

By a super-bovine exertion the Zebu tore up by the roots the tree to which it was attached and chased its tormentor round the garden, which was extensive enough to admit of an exciting chase round the trees. Finally Rossetti was enabled to escape from his pursuer whose freedom of movement had, fortunately, been hampered by the disrooted tree.”

The animal now had to be got rid of, but no purchaser could be found. Rossetti finally gave it away. Even this was not simple, as the animal had to return to the street the same way it had arrived – firmly trussed and carried gingerly through the passages of the house.

Rossetti was fond of telling stories of his menagerie. He even wrote a poem and published a funeral card when a treasured wombat died in 1869.

About the incident of the bull with the Jane Morris eyes, he was less forthcoming.

Wrote Knight: “In subsequent years, when discussing his pets past and present, Rossetti was not much given to talk of the Zebu.”

The Rossettis - Tate Britain until September 24th. In tandem with the Delaware Art Museum, where it will open October 21st until January 28th, 2024.