Every Sunday as a lad in our Midland mining town I tramped reluctantly to the Victorian chapel my family attended, for Sunday School - a couple of hours of bible stories and choruses. But each time I went though the doors, I was cheered up by something I saw on the foundation stone cemented into the brickwork.

"This stone was laid by Boaz Bloomer" it said - and never failed to raise a smile. I might have to endure the hated Sunday School, but at least I wouldn't have to go through life answering to such a silly name. Boaz was bad enough. But Bloomer too - what an odd handle.

Names have fascinated me ever since. Mine seems pretty normal to me, but you'd be surprised how many people struggle with it. To make things easier, when giving my name to hotel clerks or bureaucrats, I instinctively add "like darkness, but with an H". It’s a 50:50 shot whether this helps or hinders, but officialdom nearly always struggles to get it right.

Unusual names just seem to leap out at me in the most unexpected moments - which is why I stopped in my tracks last week while strolling away from an absorbing visit to the Imperial War Museum in Lambeth. We had toured the excellent, but chilling, Holocaust display and afterwards my wife and I needed a more cheerful experience, so we set off to find lunch in nearby Lower Marsh.

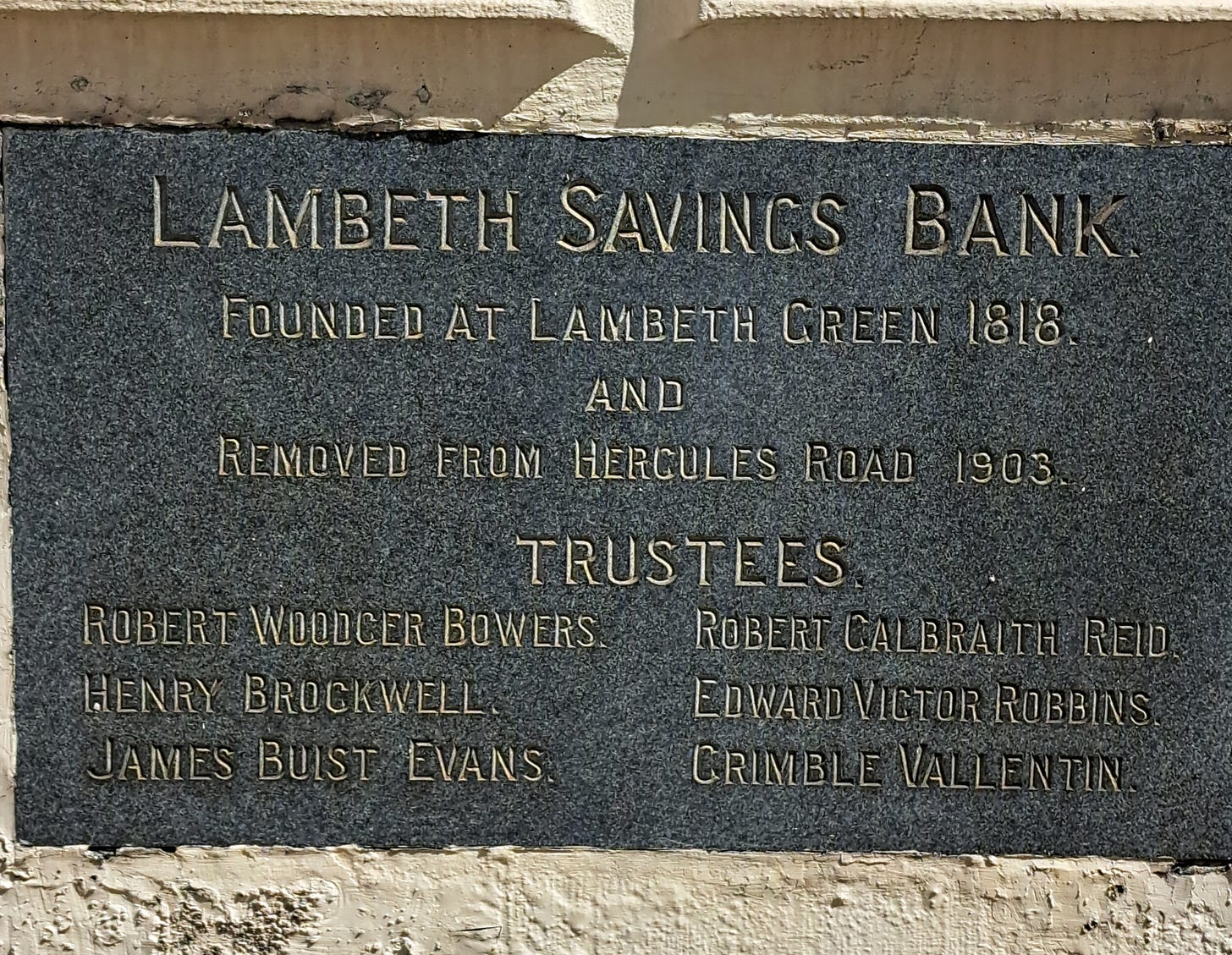

After we turned into Kennington Road, a few buildings past the Three Stags pub, a small plaque set in the wall of a rather neglected office building caught my eye. It’s a relic of the Lambeth Savings Bank, which had moved there from nearby Hercules Road when displaced by the widening of the rail tracks at Waterloo. Savings Banks were wonderful Victorian institutions, encouraging thifty habits and giving working folk help to put something aside for hard times or old age. These were the days when banks knew about money and could be trusted with it. The plaque commemorated the names of the bank’s Trustees and what a stout bunch of local worthies were on its Board. These were men from the days of self help and community endeavour, who would have had no truck with their bank peddling spivvy insurance contracts or credit cards with 39% APR.

Why do I think that? Well just look at the names. Robert Woodger Bowers. James Buist Evans. Robert Galbraith Reid. You don't get rock-solid names like those on the Board of your local savings bank these days. Come to think of it, you don't get local savings banks at all - that's another of my pet hobby horses, but we'll leave it for another day. I did a little digging in local newspaper records. Bowers, I discovered, ran a local printing business. Evans was a “bill discounter” loaning businesses cash against their invoices, and Reid was the local Lambeth doctor. All exactly the reliable individuals you might expect to be supporting a local savings institution. And for many years - though not mentioned on the plaque - the Archbishop of Canterbury was the Bank President.

What really caught my eye was the last name on the plaque. Grimble Vallentin. What a find. That's a real Boaz Bloomer of a name - and worthy of some further research. And so it proved.

Grimble was indeed a fine, upstanding chap. Like the rest of the Bank trustees he was a local businessman, a gin distiller by trade and not just any distillery. Founded in 1720, Daun and Vallentin was then the oldest established “rectifying” distillery in London. Rectifiers were the final stage of the drinks pipeline. They bought spirits in bulk and then handled the bottling, selling, advertising and marketing to the retailers or public houses. By the time of the Lambeth Savings Bank move to Kennington Road, Grimble had thrice been Master of the Worshipful Company of Distillers and was a Chevalier (knight) of the Belgian royal house, in recognition of his services in organising the British contingent at the 1894 Antwerp Exhibition.

Grimble Vallentin remained a respected Lambeth businessman until his death in 1911 and soon afterwards the Bank itself was absorbed, first into the London Savings Bank and then by various mergers into the Trustee Savings Bank of recent memory. Since then of course TSB has been subsumed into Lloyds Bank.

A sad codicil

So a chance glimpse of an unusual name inspired a bit of research which led me to a brief, but interesting, vignette of South London social history. Well worth a little light Googling on a rainy afternoon. However, there was more - a sad codicil to this tale and one which takes us back to the building I had left just a couple of minutes before spotting the plaque.

Inside the IWM there is a gallery, funded by Lord Ashcroft, which tells the story of 250 recipients of the Victoria Cross, the ultimate military gallantry award and of the George Cross, its civilian equivalent. One of the tributes is to a Captain J F Vallentin of the 1st Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment who fell in the battle for Zillebeke, Ypres, in November 1914.

He was not a man who immediately appeared to have Lambeth links. But the surname was intriguing and it turns out John Vallentin was Grimble’s son. After service in South Africa, John had remained in the Army and at the outbreak of WW1 was in one of the first waves of troops sent to the Front. The citation for the award of his VC said: “He led an attack under very heavy fire. He was struck down but rose again to continue the attack. He was killed but the capture of the enemy trenches was due to the confidence of his men in their captain, which arose from many previous acts of bravery.” Out of 96 men who were in the attack led by Captain Vallentin only 16 returned. He was hit by four bullets while he insisted on fighting on.

So there they are, the two Vallentins - remembered still, in their different ways, on either side of the A302, St George’s Road.

Postscript

Boaz, for those who are not intimate with bible stories, was the man who volunteered to marry Ruth when she was found gleaning corn in his field, while trying to support her mother-in-law. If you are interested in the other unusual names on the Savings Bank plaque : Buist derives from a Scots word for “ownership” and was used as a name for marks or brands on cattle; Woodger derives from an old English word for wood-cutter and Galbraith apparently meant “British foreigner” to Irish gaelic speakers and is the name of a Scots clan.

Why don't you just say Harkness like the rose 🌹?