How a unique memorial to the fallen was lost in a battle of political egos

Plans for a Gallery of Britain’s war art were scrapped after a bureaucratic feud

It’s Poppy time again. Collectors from the Royal British Legion are out and about and it’s likely that more than £45m will be raised to support those lost or wounded in military conflict and their families. The public remains loyally fond of the Poppy Appeal which reminds us, each November, of military sacrifice .

This time of year also reminds me of a significant lost opportunity to establish a permanent artistic memorial to the sacrifices of war – one which would have housed the unique and priceless results of Britain’s forward-thinking Official War Artist scheme from WW1, in a permanent, poignant setting. Yet it was never built because of an epic tussle between two massive egos, who sat at the top table of Government.

In the final two years of WW1 and during the Peace process which followed, the innovative Official War Artist programmes of Britain and Canada - both run from London - were a conspicuous success, in terms of the volume of work produced and in the enduring quality of the images. From a tentative start, confidence and ambition blossomed among those who selected and managed the artists until they had enabled a new genre of war coverage to establish itself. It was an initiative which is admired to this day and which continues into the conflicts of the 21st century.

As one writer put it less than a decade after WW1 ended: ‘Never before had so much official and state patronage been given to British artists.’[1] Their legacy is a colossal collection which documents war in a way which was never possible before. The artwork covers Europe, Africa and the Orient on land, sea and in the air. Yet today, where can this legacy be viewed?

On Remembrance Sunday our eyes will be on the Cenotaph in Whitehall, the simple, austere monument designed by Edwin Lutyens as a focus of national memorial ceremonies. But the Cenotaph is hardly a suitable focus of everyday remembrance, situated as it is in one of the capital’s busiest streets and the constant centre of protest and demonstration aimed at nearby Downing Street and the surrounding Government offices. It is not a place of peaceful contemplation.

The Cenotaph was not even planned to be permanent. The one unveiled in 1920 and seen in the surviving black-and-white photographs of King George V and his Ministers at an event named Peace Day and held in July was built of wood and plaster. Only a national campaign for a permanent version persuaded the authorities to construction today’s Cenotaph a few months later.

Would a national Hall of Memory, elegant and peaceful, have been a better focus of reflection? There were many who thought so - and even before the Armistice, while millions of British troops were still fighting on the Continent, a Government unit was planning a much more significant and educational memorial, using paintings, drawings and sculpture created by official war artists.

Today the majority of the British WWI artwork, some 3,000 paintings and drawings, is in the custody of the Imperial War Museum. However, with more than 85,000 artefacts in its collection, the IWM normally displays only a limited number of examples. The remainder is in storage.

Things could have been very different. The original vision was a far-sighted plan to erect a Pantheon to the fallen, housing the best British war art - some especially commissioned. It could have been an indelible tribute to the war dead and the millions who served - and a permanent reminder of the cost of war. Long before peace was a prospect, there was a realisation among some involved in the War Art project that a collection of historical significance was being created and that it could serve not just its original propaganda purpose, but also to commemorate those who fought and particularly those who died. War artists such as William Orpen, Christopher Nevinson and Muirhead Bone were engaged not just in an act of witness, but of remembrance in the making. Artists had painted war before, of course, but mainly after the fact and almost always to celebrate the victors. What made the official war artist programme, created in 1916, unique was that the artists were working in real time and often alongside those doing the fighting - and dying.

War artists engaged not just in an act of witness - but of remembrance in the making

Thanks to them we have achingly poignant works such as John Singer Sargent’s “Gassed” (see above), Nevinson’s “Paths of Glory” and the most extraordinarily varied catalogue of all from William Orpen, who produced works in many styles, from formal portraits to pieces such as “Dead Germans in a trench” and was also the official artist at the Versailles Peace Treaty negotiations.

The clearest vision of how the paintings could be used to honour the fallen formed in the mind of Lord Beaverbrook (Max Aitken) – a Canadian-born politician and newspaper owner who played a significant role in British war art.

Beaverbrook was a schemer and in 1916 he helped oust Asquith as British Prime Minister and install David Lloyd-George in his place. His reward was a peerage and the post of Minister of Information. He had already been supervising the Canadian war art project as an honorary Colonel in the Canadian army and was working on a plan to house the Canadian paintings in a huge War Memorial gallery in Ottawa, the Dominion’s administrative capital.

The Pantheon, in the Latin Quarter of Paris, was the inspiration for Beaverbrook’s Memorial Gallery. In the main gallery, Beaverbrook visualised ‘a nucleus of vast decorative panels’ while elsewhere in the building would be displayed ‘a comprehensive collection of paintings, drawings and engravings of war subjects, portraits of generals, statesmen and Canadian VCs, works of sculpture.”

The Dominion’s modest finances, coupled with the fact that there had been a considerable disquiet among Canadians about the extent of their involvement in the European War, made the project controversial. Beaverbrook’s answer was to under-write some of the costs himself. In addition Beaverbrook formed a registered charity through which the Canadian War Artist programme operated, to accept money from himself and receive substantial income from exhibitions of paintings and war photographs mounted by the Canadians in London and elsewhere and also by the sale of publications produced by the Fund.

It was this energetic, buccaneering approach which impressed Lloyd-George, who decided to harness this entrepreneurial flair to the British propaganda effort and appointed Beaverbrook to be Minister of Information. Beaverbrook handed day-to-day control of the war artist programme to a new charitable body which he named the British War Memorials Committee. Alfred Yockney, who later became the first curator of the IWM, served as the BWMC secretary and treasurer.

The concept of establishing a charity to help fund the BWMC followed the model Beaverbrook had employed for the Canadians and it came at a personal cost. He pumped his own money into the BWMC by way of a loan ‘to meet immediate liabilities’ and to enable arrangements for a complete scheme to evolve. ‘As regards finance,’ the Minutes of the first committee meeting reported ‘the Chancellor of the Exchequer has agreed that the net proceeds from lending cinema films and holding exhibitions … maybe be used for charitable purposes, and Lord Beaverbrook has named the BWMC in connection with this revenue.’[2]

The first exhibition, the income from which would go to the BWMC, was of William Orpen’s paintings ‘held under the auspices of the Ministry of Information at Agnew Gallery in New Bond Street. Proceeds will go to the British War Memorials Fund.’ It was a profitable start. Orpen’s show became a hot ticket. More than 9,000 visitors paid to view the paintings in just six weeks.

Lloyd George was such a fan of the idea, that he personally solicited the services of John Singer Sargent writing: “If you will undertake this task you will be doing a work of great and lasting service to the Nation.”

Beaverbrook next secured backing for the vision of a Hall of Remembrance from the Prime Minister himself. Lloyd George was such a fan of the idea, that he personally solicited the services of John Singer Sargent to paint one of the four main ‘super pictures’ which Beaverbrook wanted to hang in the main Gallery. LG wrote to Sargent on Downing Street notepaper: ‘These pictures will be preserved in a Memorial Gallery in London as a series of immortal works . If you will undertake this task you will be doing a work of great and lasting service to the Nation.’[3] Sargent was obviously convinced the Memorial Gallery was an official scheme approved at the highest level and the painting became Gassed, his magnificent six metre canvas depicting lines of soldiers being led blind-folded to dressing stations, after a mustard gas attack. The painting was completed in 1919 and is now in the ownership of the Imperial War Museum. It is the only one of the four planned “super pictures” to have been completed.

Beaverbrook’s plan was in full swing. The BWMC appointed an Executive Committee of art advisers, who met at the Norfolk Hotel, which had been commandeered as Ministry of Information office space, to consider proposals for additional artists and to review progress on work already approved. This period was the most productive and organised for the art programme. The committee co-opted additional members from time to time, but the core group was art critic P.G.Konody, Beaverbrook’s adviser on the Canadian scheme, Campbell Dodgson, of the British Museum and Muirhead Bone. These three were the principal talent-spotters of potential war artists. Another regular attender was Robbie Ross (1869-1918), Canadian-born art critic and sometime art dealer who had been Oscar Wilde’s lover and was his literary executor. Arnold Bennett, the novelist turned propagandist, also often attended.

For Beaverbrook, with the ear of the Prime Minister and the backing of Chancellor, the object of his plan must have seemed within grasp. Yet, just across Westminster, disaster loomed. One of Beaverbrook’s ministerial colleagues took an altogether different view of the BWMC and its ambitions – and saw Beaverbrook as a trespasser on his own department’s turf.

Sir Alfred Mond (1868-1930), who became Lord Melchett in 1928, was a member of an industrial dynasty, hugely wealthy and a significant art patron. Mond had been appointed First Commissioner of Works and Public Buildings, in which role he had proposed to the Cabinet that a National War Museum (subsequently re-named the Imperial War Museum) should be created. Mond was appointed chairman of its steering committee having written his own brief for the Museum project and felt he had an exclusive mandate to collect war art. He was furious when Beaverbrook sent him a letter advising him of the creation of the BWMC’s charity arm and of his intention to commission leading artists to paint specifically for his proposed Memorial gallery scheme.

Mond was particularly irked to hear of the Chancellor of the Exchequer’s apparent agreement that the charity could generate funds for the art scheme by licensing and exhibiting war paintings which had been paid for by public funds. Believing Beaverbrook was subverting his Museum plan – and his authority - Mond fired off a thundering four page response to Beaverbrook’s suggestion that the proposed war museum should steer clear of war art. ‘The creation of the War Memorials Committee, which I understand is a private organisation of your own and not a Government department, creates an entirely novel position which, I believe, is without foundation.’ Mond continued, bluntly: ‘It will obviously be impossible for me to fall in with your views that the Imperial War Museum should simply stop collecting pictures’[4]

This was not simply some Ministerial spat over bureaucratic boundaries. Mond was the product of an English public school and Cambridge University and considered himself an aesthete and a man of culture. His father, Ludwig, had built up a significant art collection which he donated to the National Gallery. Later, in 1924, Sir Alfred endowed the Gallery with sufficient funds to house his father’s collection. Mond was also an appalling snob. Beaverbrook, by contrast, had started life as an errand boy, failed to get into any Canadian university and then flunked a law course. Perhaps worst of all he was, self-confessedly, not an art expert.

There followed a classic British bureaucratic compromise. A new joint body, named the Pictorial Propaganda Committee, was established. Thus it was that the two antagonists, Mond and Beaverbook, found themselves, face-to-face, across the table at meetings of the PPC, but it was Mond who was ultimate victor, as the Imperial War Museum became the eventual depository of war paintings.

Although his ultimate ambitions were never realised, Beaverbrook’s influence on the war artist programme was immense and much of the art which is in public ownership today, on both sides of the Atlantic, would never have been commissioned without his drive and determination.

The Hall of Remembrance proposal is almost forgotten today yet, as Richard Cork wrote in an article in Apollo magazine ‘It would undoubtedly be cherished today as a profound memorial to the tragedy of the First World War ’[5]

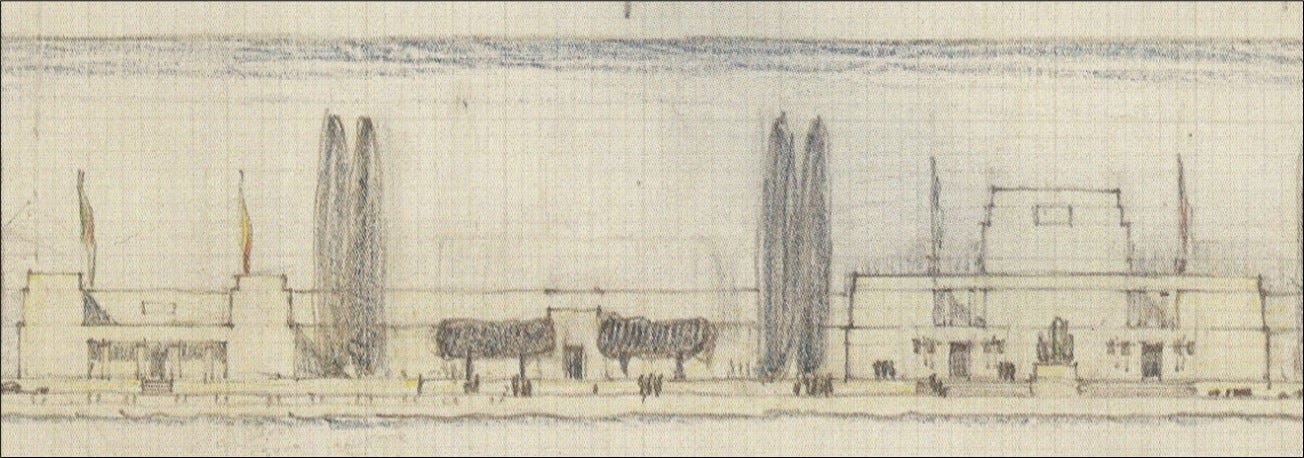

An architect was chosen, through the personal recommendation of Britain’s first ever official war artist, Muirhead Bone. Charles Henry Holden was working, with army rank, for the War Graves commission on plans for cemeteries. There is some surviving archival evidence of what Holden had in mind, including a working sketch of the main elevation which is in the archives of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA). There is sufficient detail in the sketch for us to glimpse the monumental style and elegance which Holden could have brought to the Hall of Remembrance. Holden ran the design office of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and produced designs for almost 70 of the CWG monuments.

We know, too, the approximate location at which Beaverbrook wanted to construct the monument. It was intended for a prominent site on Richmond Hill from which it would have had far-reaching views over London. Most intriguing of all, perhaps, there is also a comprehensive list of the planned works in Government archives – some of which were completed.

Beaverbrook’s Canadian memorial project progressed further – but met the same eventual fate. His chosen site, a hill named Nepean Point in Ottawa, overlooks the Ottawa River, Canada’s Parliament and the Canadian Museum of History. Unoccupied for decades after World War I, the location eventually became the site for the National Gallery of Canada in 1988.

Paul Konody, as ever Beaverbrook’s arbiter of taste in the world of art, provided the name of an ideal candidate to act as architect – a rising young British architect, Edwin Rickards, who was responsible for London’s Methodist Central Hall, built opposite Westminster Abbey in 1911.

The entire collection of World War I Canadian war art consists of almost 1,000 works by more than 100 artists – the majority of whom were British. The works are now conserved by the Canadian War Museum, but the vast majority are in storage. However, visitors to the Canadian Parliament in Ottawa are able to gain at least an impression of what might have been. Eight of the main paintings commissioned and completed for the still-born Canadian War Memorial project were hung around the walls of Canada’s Upper House, the Senate, in 1921 and were the subject of a re-dedication ceremony in 1998 on the 80th anniversary of Armistice.

[1] Frank Rutter The Outline of Art, Editor: Sir William Orpen, Chapter XXIV Art During the Great War (London, George Newnes, 1924), p. 608.

[2] London, Parliamentary Archive, MS BWMC Minutes, 29 May 1918, Beaverbrook Papers.

[3] London, Parliamentary Archive, MS David Lloyd George to John Singer Sargent, 16 May 1918, Beaverbrook Papers.

[4] London, Parliamentary Archive, MS Sir Alfred Mond to Lord Beaverbrook. 29 May 1918, Beaverbrook Papers.

[5] Volume CLXXIX No 616, January 2014.

By the way, do "subscribe" to my posts if you would like to see more. It would be a great boost to my writing ego!!

Hi Billy - I used it in my dissertation too! What are you studying and where?

I can't recall where I found it now. But if you can lift it from my article you are very welcome.

Peter