It is a night of music, wine, sponsored cocktails and cultural chit-chat and gossip - an unmissable date on the cultural calendar when Artfund unveils its annual Museum of the Year. The 2024 reveal, held in the National Gallery, was if anything, glitzier and happier than ever, as we all agreed that - SURELY, whatever they said about finances before the election - Keir Starmer’s new Government will bring better days for arts and culture.

Well, we’ll see. I hope that new Culture Minister Chris Bryant, who was partying with the rest of us at MotY, finds a way to persuade Rachel Reeves to channel more cash into culture. But I am not optimistic.

A few days after the party I visited a little-known South Coast venue to see how a museum can cope on the bread-and-water diet available when you only have modest local donations and unpaid staff to keep the doors open.

Chances are you have never heard of the Bournemouth Natural Science Society and the odds are greatly against you ever having visited its Victorian Grade II premises on a traffic-packed thoroughfare close to the town centre. From the outside the Museum has a rather abandoned air, in common with other faded mansions which lurk among the huge pine trees on the East Cliff. Most have now been divided to house elderly tenants or have been abandoned altogether to await their turn to be demolished and and to re-emerge as 21st century blocks offering flats with seven figure price tags.

The Italianate BNSS museum building, bought 100 years ago by local enthusiasts for science and discovery, will hopefully be assured of a different future. I’d been meaning to visit BNSS for several months, since I spotted its rather too discreet sign on a visit to Bournemouth’s spectacular Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum, just a few hundred yards away overlooking Bournemouth beach.

It may be anonymous outside, but once through the doors BNSS was a revelation, alive with a disparate clientele ranging from the elderly, armed with NHS walking sticks, tapping their way through the themed display rooms, down the age groups to giggling and squealing teens. The reason for the squeals became apparent in “Animals and Birds” where the faded taxidermy displays had been joined by a chap called Jim who brought with him a travelling zoo of insects and snakes. He holds court at a large table in the centre of the room, piled high with what looks like a display of fridge storage boxes, and is surrounded by teenage acolytes stroking snakes and cuddling large hairy spiders.

The plastic vivaria were teeming with further exotics and I am, it seems, their prey. “Would you like to hold a snake?” asks Jim. Very kind, but no thanks. “A millipede? They have really sticky feet” It’s OK, honestly. “What do you think of this?” He thrusts, in my direction, what looks like a spikey cucumber, about four inches long, clinging to a large leaf. It turns out to be a giant caterpillar and Jim has a (dead) example of the enormous moth it will become. Less squeamish than me, his acolytes are fondling snakes in vivid shades of yellow, green and pink – Jim has a marvellous menagerie and they all seem beautifully healthy and well-kept in their towers of Tupperware.

I’m curious. Does he have a large breeding programme? “Oh no, I get them on-line. You can get anything on-line” I express astonishment, but the acolytes seem unsurprised. After all they are the on-line generation – where else would tomorrow’s herpetologists and entomologists hunt for specimens?

Elsewhere in “Animals and Birds” are displays more typical of museums of a century ago when BNSS was moved to this Gothic mansion - previously the home of the Cassel family - in 1920. Then taxidermy reigned as the primary means to display flora and fauna and on a large walnut table there is a gathering of woodland creatures, craftily animated before being frozen in time by an Edwardian curatorial spell. A computer-printed sign gives a nod to 21st century fashions for accessibility - permitting touching and photography and offering today’s delicate viewers the comfort that “These animals all died naturally”. Squirrels prance and moles squint and an angry-looking fox has a large green snake clinging to its back. Ah, yes, a nod to Aesop’s tale of the fox who carried a snake across a swollen river - these volunteer curators enjoy a little joke! The fox’s passenger is certainly not one of Jim’s troupe and the pair look more the sort of thing you might see in a glass case in an old country pub.

I make my way upstairs to Archaeology, curious to discover more about the history of this area of the South Coast. On the way I pass a small notice, redolent with Lewis Carroll appeal. “Curiosity Cupboard…please look inside” I pull open the wooden door, as invited. Blimey! There’s some revolting stuff in there – all safely pickled in specimen jars, with skin-crawling, stomach-turning labels. I start to read them, but move hurriedly on when I get to a jar of grubs which can eat a horse…from the inside! Too much information, but how my pre-teen grandsons would love the ghoulish detail.

At the top of the building, I come face-to-face with one of the BNSS’s early stalwarts, the extraordinary Heywood Sumner, first a lawyer and then for three decades a successful artist. Finally, on early retirement to Bournemouth for his wife’s health, Heywood began decades of excavation, discovery and mapping which preserved pre-Bournemouth history from the rapacity of the Victorian and Edwardian developers who built this South Coast resort. Heywood’s photograph and a brief biography marks the entrance to Archaeology - a room of pots, Roman artefacts and curios from around the world.

Sadly the builders of Bournemouth had little interest in the artefacts unearthed by their navvies digging the foundations of what has now become a conurbation of 400,000, sprawled along the coast from Christchurch to Poole. Roman and pre-Roman pottery was either chucked aside or used for target practice by bored workmen. Heywood turned the workmen into a significant archaeological resource by offering cash for interesting finds. Several BNSS cabinets are packed with his booty.

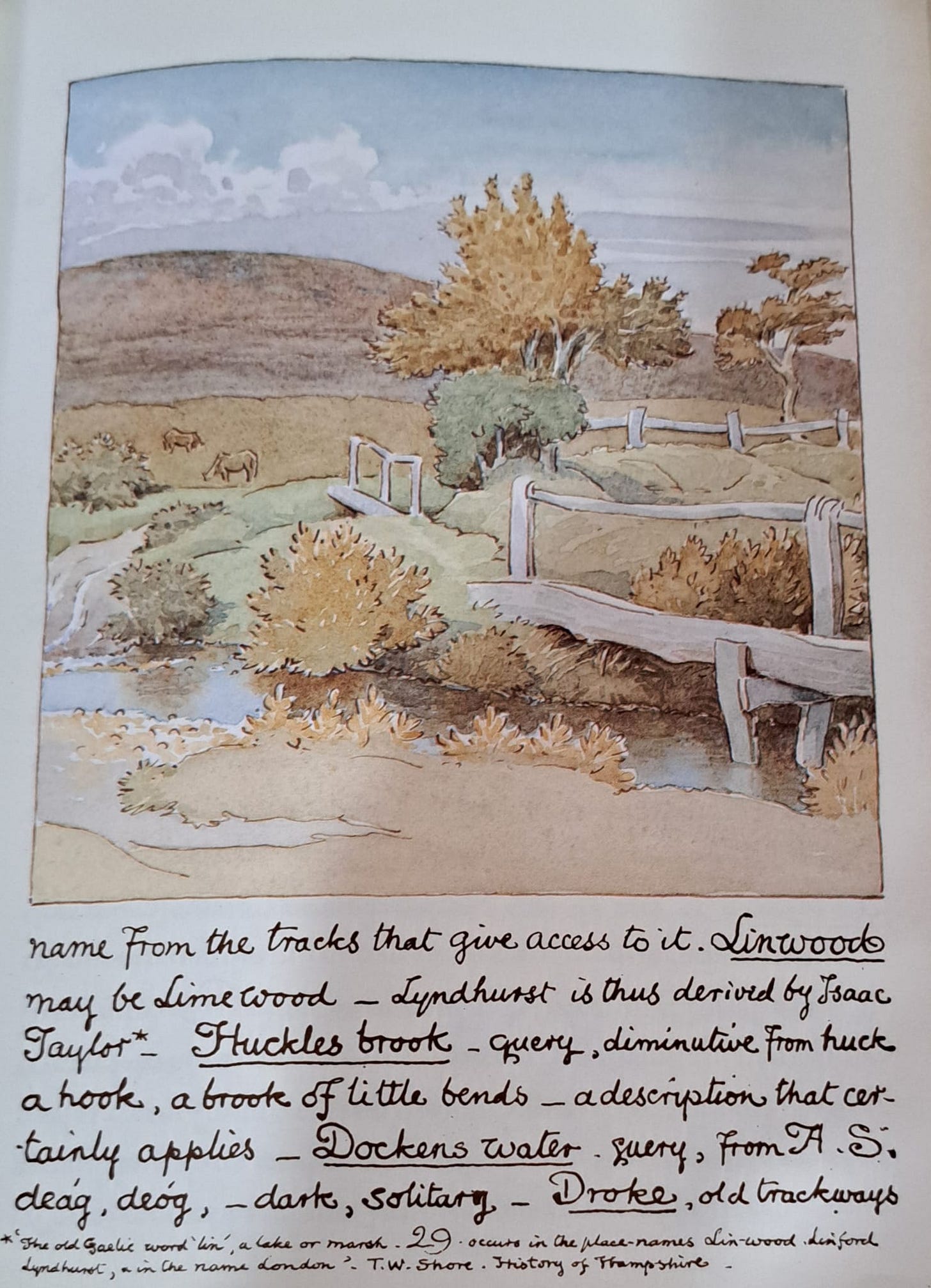

Heywood’s other triumph was the creation of beautiful maps and books illustrating the area’s history and topography. In the manner later adopted by Albert Wainwright for his Lake District guide books, Heywood hand-wrote the text and on the same pages illustrated the books with charming watercolours. The result is far more colourful and absorbing than Albert’s grumpy little volumes. Sometimes, a helpful volunteer tells me, modern reprints of Heywood’s work appear in second-hand shops. I resolve to log on to Abe Books the moment I get home.

There is much, much more to see and I will return to BNSS one day. I completely failed to visit the shell collection or the geological section - such a gem that it was apparently described in 1914 by the Keeper of the Cambridge University museum as "one of the best in the world” at that time. I did spot their Egyptian sarcophagus through a doorway as I hurried by, frustrated that my available time made this visit so brief. BNSS had its contents CT-scanned and the head of the mummy has been recreated. He’s on display in the foyer, so I gave him a nod as I left.

Back in the main hall, visitors continue to arrive although there is only 30 minutes left of the 10am-4pm opening hours. The helpful desk volunteer seems delighted with today’s turnout. “It’s not usually this busy, but it’s lovely to see them. We are one of the few Museums with live insects…well, intentionally, anyway” BNSS is an entirely volunteer organisation and the poor state of the building and the chummy, home-made signage means she does not have to explain that money is tight. In fact BNSS is only open on Tuesdays for most of the year and even then it is a struggle to get all the galleries and reception manned.

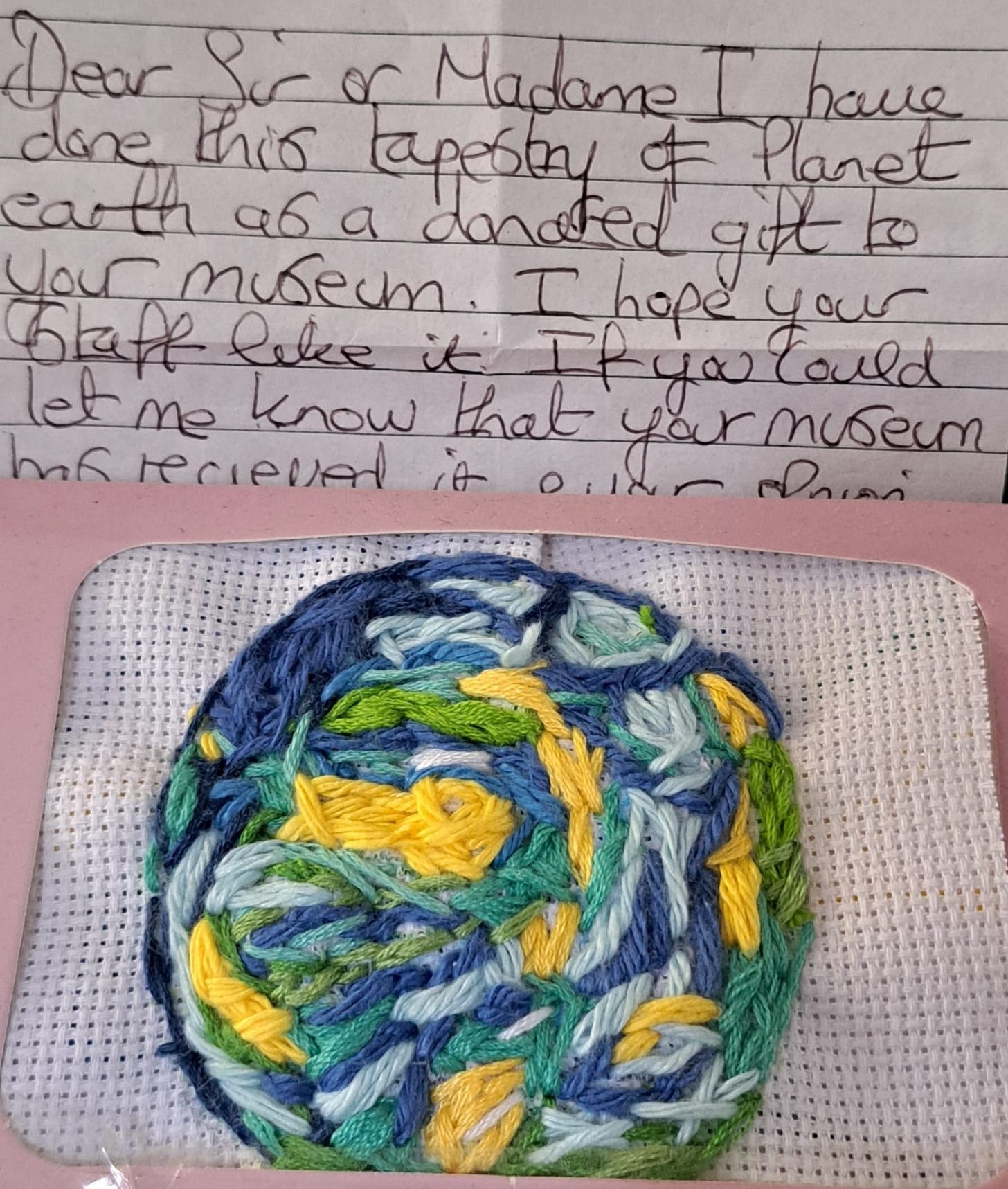

It clearly has a devoted following. There is a display of thank you letters in the Hall - including a hand-knitted model of Planet Earth attached to a polite note in a childish hand.

If you would like to drop in to this enchanting museum, there’s much more opportunity in August when – as Bournemouth hums with its summer crowds – BNSS will open three days each week. They might also pray for a little rain on their opening days - it usually works wonders for museum and gallery attendances.

BNSS Museum has a free entrance policy. Frankly, I can’t fathom why they don’t charge a modest entrance fee, especially for hectic August opening. But there is a donations box and the receptionist is equipped with a card machine to cope with the small retail offer. I use it to beep a tenner in to their coffers, but I feel rather mean and afterwards wish I had given more.

The shrieks from “Animals and Birds” ring in my ears as I leave. Jim is obviously still wowing young visitors by producing exotic creatures from their sandwich-box lairs. This is exactly how it ought to be in BNSS and in thousands of other collections across this land. After all, archaeology and palaeontology collections are not really there for old fossils like me. Long-dead collectors, who assembled museums like this, were thrilled and excited by every stone age axe, or Roman lamp or Saxon cooking pot they truffled out of the heaths and cliffs of Dorset or carried back from Egyptian digs. They did it not just out of reverence for the past, but to inform and inspire the future.

BNSS might be a bit scruffy and crumbly and amusingly eccentric, but it is keeping alive the thrill of learning by exciting young imaginations. And surely that’s exactly what museums - from MotY winners down to the modest BNSS - are for.

Bournemouth Natural Science Society, 39 Christchurch Road, Bournemouth BH1 3NS Tel: 01202 553525 Email: contact@bnss.org.uk.

Usually open each Tuesday 10am-4 pm and extra days in August (check in advance which ones). Oh, and it’s free to enter - but give them a donation, please!

That's very kind, Portia! Glad you enjoyed it.

I love your witty voice and the details here, Peter! I feel as though I walked through the museum with you, smiling as you occasionally whispered clever words about your observations. 😎😎😎